Battery Basics

A Deep Cut on the Li-ion Battery's Inner Workings

Hi everyone! This first issue is a primer on likely the most recognizable of energy storage technologies: batteries. They come in all shapes and sizes (and chemistries, capabilities, etc.) – complexities we’ll get into with future posts. To narrow our scope for now, we’ll focus on the current royalty of battery technologies: the versatile lithium-ion battery (“Li-ion” battery).

Batteries are important now, but will become even more so.

You can already find batteries powering smartphones, cars, and even entire neighborhoods. For context, U.S. battery storage more than tripled in 2021, and the IEA anticipates capacity will increase by more than 34x by 2030 compared to 2020. Batteries are so popular because they allow us to temporally decouple energy collection and consumption. Translation: they allow us to store previously collected energy to be used at a later time.

As the world transitions to renewable energy, we’ll need to rely on energy storage technologies like batteries more and more. One frequent criticism of solar and wind-based electricity generation is that it is intermittent -- the energy supply is disrupted at night, on cloudy days, or when there is no wind. For solar energy, this problem is clearly illustrated in the chart below. Solar generation is highest in the middle of the day while energy demand is mismatched, rising in the early morning when people wake up and peaking in the evening when they return from work.

Energy storage systems, batteries or otherwise, can smooth out the intermittency of renewable energy resources. These systems can store excess energy when supply is greater than demand and then discharge that energy when demand is greater than supply, like on a cloudy, windless day.

Battery cells are made of four fundamental parts.

The basic unit of a battery is called a cell. There are four main components of a cell: two electrodes (a cathode and an anode), an electrolyte, and a separator.

Cathode, the positive electrode: Electrons flow towards the cathode while the battery discharges. Common Li-ion battery cathode materials are Lithium Nickel Cobalt Aluminum Oxide (NCA), Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide (NMC), and Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP).

Anode, the negative electrode: Electrons flow away from the anode during battery discharge. The most common anode material for Li-ion batteries is graphite.

Electrolyte, the movement medium: The electrolyte allows Lithium ions to travel between electrodes to balance the electron flow in the chemical reaction (more on this later). A common electrolyte for Li-ion batteries is lithium hexafluorophosphate salt mixed in with some other organic carbonates.

Separator, the… separator: The separator prevents cell short circuits by physically separating the anode and cathode. It allows lithium ions to pass between the electrodes, but not electrons, which improves the safety of the system. They are typically a polymeric material.

The flow of electrons between electrodes drives battery functionality.

Energy stored in the battery is released through a chemical reaction that causes a flow of electrons from the anode to the cathode.

This particular type of chemical reaction, where electrons are transferred from one material to another, is called a reduction-oxidation (“redox”) reaction. A full redox reaction is composed of two half-reactions – one at each electrode. When a battery charges, the cathode loses its electrons via the oxidation half-reaction, while the anode gains those same electrons via the reduction half-reaction. While the battery discharges, this process reverses.

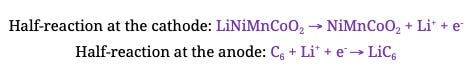

For example, in a Li-ion battery with an NMC cathode and graphite (C6) anode, the half reactions at each electrode while charging would be:

In words, the lithium ions start off intercalated, or nestled, within the cathode oxide layers in a very stable state. When the battery is connected to an energy source to charge, the electrons at the cathode are pulled away to the graphite anode. Since the electrolyte separator does not allow electrons to travel directly through the cell, they flow along the wired circuit to collect at the anode.

At the same time, positively charged lithium ions also leave the cathode and travel to the anode to balance the flow of negative electrons. The electrolyte separator allows the ions to pass directly through the cell to the anode, where they are stored between the graphite layers. Once the anode’s graphite layers fill up with lithium ions and electrons, the battery is fully charged.

While discharging, the above process reverses. As a reminder, the most stable state for the lithium is to be in the cathode’s metal oxide structure, so the battery stores energy by trapping the lithium ions and electrons in the higher energy state. Then, when a load is connected, such as a light bulb, the electrons and Li-ions automatically start flowing back to the cathode, since it’s the more stable state. This flow of electrons from the anode to the cathode powers the light bulb! Here are the half-reactions happening at each cathode for a discharging battery:

This more detailed diagram of a discharging battery might make things clearer:

Combining the charging and discharging reactions together with a double-headed arrow to signify that the reaction runs both ways, we can characterize a battery’s operation by the below expression. Left to right is discharging, right to left is charging:

Battery performance can be evaluated by discharge power, charging speed, and energy capacity.

Batteries are measured by many metrics, but below are some that will get us started.

Discharge Power, measured in Watts (W), is the rate of energy flow from the battery during discharge. 1 Watt is pretty small, they are usually referred to in larger increments like kilowatts (one thousand Watts, “kW”), megawatts (one million Watts, “MW”), and gigawatts (1 billion Watts, “GW”).

Power is a function of current (measured in amps) and voltage (measured in volts) through the equation Power = Current * Voltage.

Charging Speed, also measured in Watts, is the rate of energy flow into the battery while charging, and by extension, is a measure of how quickly the battery can be charged.

Energy Capacity, measured in Watt-hours (Wh), is the total amount of energy that can be stored in a battery. 1 Watt-hour is also pretty small, so they are usually referred to in larger increments like kilowatt-hours (one thousand Watt-hours, “kWh”), megawatt-hours (one million Watt-hours, “MWh”), and gigawatt-hours (one billion Watt-hours, “GWh”).

Energy Capacity = Rate of Energy Flow (a.k.a. Power) * (Time to Fully Discharge or Charge).

As an analogy, think of electricity, the flow of electrons, as the flow of water from a hose into a bucket. The rate of water flow (power) depends on the width of the hose (current) and how fast the water is flowing (voltage). The total amount of water in the bucket at any point in time (energy), is calculated through multiplying the rate of water flow and time elapsed.

What determines the discharge power of the battery?

Remember, Discharge Power = Voltage (measured in Volts) * Current (measured in Amperes).

A major factor determining battery voltage (i.e., how fast the water is flowing from the hose) is the battery cell’s standard potential. This is a measure of how badly electrons want to travel from anode to cathode during battery discharge and is calculated by the difference in electrochemical potential of the two half reactions (the reduction and oxidation) happening at each electrode.

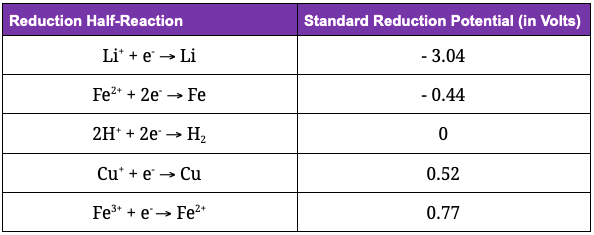

It’s fundamentally impossible to measure the potential of any single electrode – we can only measure the difference in potential between electrodes. So, scientists defined the standard hydrogen electrode as having 0V potential. This allowed them to tabulate standard reduction potentials for all kinds of materials, in turn allowing us to measure the tendency of those materials to lose/gain electrons:

By convention, all potentials are written for reduction half-reactions, so they measure the tendency of a material to gain an electron. To get the oxidation standard potential, just flip the sign!

Materials that lose their electrons spontaneously and easily will have a negative standard potential. In the above table, you can see lithium has the highest tendency to lose its electron, making it an ideal material for batteries. Materials that want to hold onto their electron will have a positive standard potential (they require a push of energy to give up their electron).

Using these tabulated values, we can now calculate the standard cell potential for any combination of electrodes through subtracting the standard reduction potentials: E(cell) = E(cathode) - E(anode)

Current, the second part of the power equation (Power = Voltage * Current) is a measure of the amount of charge flowing per second out of the battery and into the circuit. We can calculate it by dividing the battery voltage by the circuit’s resistance to electron flow. We already know what voltage comes from. Resistance comes from the load attached to the battery circuit – lightbulbs, motors, wires, etc.

Through the equations [Power = Voltage * Current] and [Current = Voltage / Resistance], we can derive: [Voltage = Current^2 * Resistance[, which is another helpful equation in the world of batteries.

When combining individual cells into larger batteries, we can increase discharge power by either increasing the voltage (by connecting cells in series) and/or the current (by connecting cells in parallel).

What determines the energy capacity of a battery?

Energy Capacity (Wh) = Power Discharge Rate (W) * Full Discharge Time (hours). It’s a measure of the total amount of work the battery is capable of doing. Increasing the energy capacity of a battery pack can simply be done by connecting multiple battery cells together, since more cells = more energy stored.

However, in reality, we can’t always just add more cells if we need more energy. For example, thicker phones with bigger batteries may not be as appealing to consumers. In electric vehicles, more batteries mean more weight, which can reduce the range of the vehicle. Adding cells also increases the cost of the battery.

Instead, much research is focused on improving cell energy density (i.e., the amount of energy that can be stored per unit mass or volume), so we can use less cells for the same energy capacity. There are two key metrics of energy density:

Gravimetric Density (Wh/kg) * Mass (kg) = Energy Capacity (Wh)

Can be improved by increasing the amount of energy that can be stored in a fixed mass, or reducing the mass that can store a fixed amount of energy.

Volumetric Density (Wh/L) * Volume (L) = Energy Capacity (Wh)

Can be improved by increasing the amount of energy that can be stored in a fixed volume, or reducing the volume required to store a fixed amount of energy.

So what determines how much energy can be stored per unit mass or volume? Let’s walk through some equations, using information we’ve already derived earlier in this post.

So, energy density is determined by how much charge (measured in Coulombs), and therefore lithium ions, a battery can store per unit mass or volume. A gram of lithium can store 13.9k Coulombs, so at 3 volts, a cell that can store one gram of lithium could supply 41.7kJ of energy (Wikipedia).

If we can find materials that can store more Li-ions in lower mass or volume, we can improve the energy density of batteries! Or, if we aren’t concerned with cost, volume, or weight, we can simply add more cells to increase energy capacity.

Anything other than energy and power capacity?

Beyond power and energy capacity, here some other performance metrics used to evaluate battery technologies:

Round-Trip Efficiency: ratio of energy put into the battery to how much comes out.

Economic Measures

$/W = cost per Watt (power output). Usually $/kW.

$/Wh = cost per Watt-hour (energy output). Usually $/kWh.

Cycle Life = how many times the battery can be charged and discharged (“cycled”) before dropping below a certain threshold of energy capacity (such as 80%).

No single battery type excels in all of these performance measures. The key to using batteries successfully is matching the battery type with the right use case by evaluating the tradeoffs between different metrics.

That’s it for now, thanks for reading! In the next post, we’ll deep dive on what the Inflation Reduction Act means for the future of energy storage.